The 11 Best Science Books of 2011

by Maria Popova

From Infinity to Fibonacci, or what religious mythology has to do with the inner workings of field science.

After the year’s best illustrated books for (eternal) kids, art, design, and creativity books, and photography books, the 2011 best-of

series continues with a look at the year’s most compelling science

books, spanning everything from medicine to physics to quantum

mechanics. (And before you raise an eyebrow at the absence of the social

and “soft” sciences, know that an omnibus of the year’s best psychology

and philosophy books is coming next week.)

After the year’s best illustrated books for (eternal) kids, art, design, and creativity books, and photography books, the 2011 best-of

series continues with a look at the year’s most compelling science

books, spanning everything from medicine to physics to quantum

mechanics. (And before you raise an eyebrow at the absence of the social

and “soft” sciences, know that an omnibus of the year’s best psychology

and philosophy books is coming next week.)

THE IMMORTAL LIFE OF HENRIETTA LACKS

THE IMMORTAL LIFE OF HENRIETTA LACKS

Rebecca Skloot is one of the finest science writers working today. In The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, one of five fantastic books about unsung heroes,

she tells the story of a woman who unwittingly shaped contemporary

science. (Though the book came out in 2010, the paperback was released

in 2011 so, hey, it counts.)

Rebecca Skloot is one of the finest science writers working today. In The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, one of five fantastic books about unsung heroes,

she tells the story of a woman who unwittingly shaped contemporary

science. (Though the book came out in 2010, the paperback was released

in 2011 so, hey, it counts.)

When Henrietta Lacks

(1920-1951), an African-American mother of five who migrated from the

tobacco farms of Virginia to poorest neighborhoods of Baltimore, died at

the tragic age of 31 from cervical cancer, she didn’t realize she’d be

the donor of cells that would create the HeLa

immortal cell line — a line that didn’t die after a few cell divisions —

making possible some of the most seminal discoveries in modern

medicine. Though the tumor tissue was taken with neither her knowledge

nor her consent, the HeLa cell was crucial in everything from the first

polio vaccine to cancer and AIDS research. To date, scientists have

grown more than 20 tons of HeLa cells.

Skloot weaves a fascinating and tender detective story about HeLa’s

legacy through the discovery of Henrietta’s youngest daughter, Deborah,

who didn’t know her mother but who always knew she wanted to be a

scientist. As Skloot and Deborah, infinitely different yet united by the

shared quest for answers, unravel one of the most absorbing mysteries

of modern science, we also get a rich and sensitive tale about family,

community, and the dark side of society’s capacity for exploiting its

poorest and most vulnerable members. The book, one of the decade’s most

excellent and ambitious science-and-so-much-more reads, is currently

being made into an HBO movie by Oprah Winfrey and Alan Ball.

Good science is all about following the data as it shows up and letting yourself be proven wrong, and letting everything change while you’re working on it — and I think writing is the same way.” ~ Rebecca Skloot

In an interview with Skloot,

David Dobbs offers a fascinating behind-the-scenes look at how the book

came to life — a must-read for anyone interested in the intricacies of

intelligent inquiry and storytelling, in science and in general.

THE BEGINNING OF INFINITY

THE BEGINNING OF INFINITY

Since time immemorial, mankind’s greatest questions — what is reality, what does it mean to be human, what is time, is there God

— have endured as a pervasive frontier of intellectual inquiry through

which we try to explain and make sense of the world, the pursuit of

these elusive answers having germinated disciplines as diverse as

philosophy and physics. But what place does explanation itself have in

the universe and our understanding of it? That’s exactly what iconic

physicist and quantum computation pioneer David Deutsch explores in The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World

— an important and wildly illuminating new book on the nature and

evolution of human knowledge. Fluidly switching between evolutionary

biology, quantum physics, mathematics, philosophy, ancient history and

more, Deutsch offers surprisingly — or, perhaps knowing his work,

unsurprisingly — plausible answers to everything from why beauty exists

to what is infinity.

Since time immemorial, mankind’s greatest questions — what is reality, what does it mean to be human, what is time, is there God

— have endured as a pervasive frontier of intellectual inquiry through

which we try to explain and make sense of the world, the pursuit of

these elusive answers having germinated disciplines as diverse as

philosophy and physics. But what place does explanation itself have in

the universe and our understanding of it? That’s exactly what iconic

physicist and quantum computation pioneer David Deutsch explores in The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World

— an important and wildly illuminating new book on the nature and

evolution of human knowledge. Fluidly switching between evolutionary

biology, quantum physics, mathematics, philosophy, ancient history and

more, Deutsch offers surprisingly — or, perhaps knowing his work,

unsurprisingly — plausible answers to everything from why beauty exists

to what is infinity.Must progress come to an end — either in catastrophe or in some sort of completion — or is it unbounded? The answer is the latter. That unboundedness is the ‘infinity’ referred to in the title of this book. Explaining it, and the conditions under which progress can and cannot happen, entails a journey through virtually every fundamental field of science and philosophy. From each such field we learn that, although progress has no necessary end, it does have a necessary beginning: a cause, or an event with which it starts, or a necessary condition for it to take off and to thrive. Each of these beginnings is ‘the beginning of infinity’ as viewed from the perspective of that field. Many seem, superficially, to be unconnected. But they are all facets of a single attribute of reality, which I call the beginning of infinity.” ~David Deutsch

In 2009, I had the pleasure of seeing Deutsch speak at TEDGlobal,

where he delivered what was unequivocally the event’s most mind-bending

talk, presenting a new way to explain explanation itself — a teaser for

the book as he was in the heat of writing it. Stay on your toes and try

to keep up:

Empiricism is inadequate because scientific theories explain the seen in terms of the unseen and the unseen, you have to admit, doesn’t come to us through the senses.” ~ David Deutsch

The Beginning of Infinity comes as Deutsch’s highly anticipated follow-up, thirteen years later, to his excellent The Fabric of Reality: The Science of Parallel Universes and Its Implications, in which Deutsch outlined the four fundamental strands of existing knowledge.

Bear in mind, this is no light beach book, nor is it an easy read,

but it’s an incredibly lucid one, the kind of book that stays with you

for your entire lifetime, insights from it finding their way,

consciously or unconsciously, into every intellectual conversation

you’ll ever have.

Originally reviewed in July.

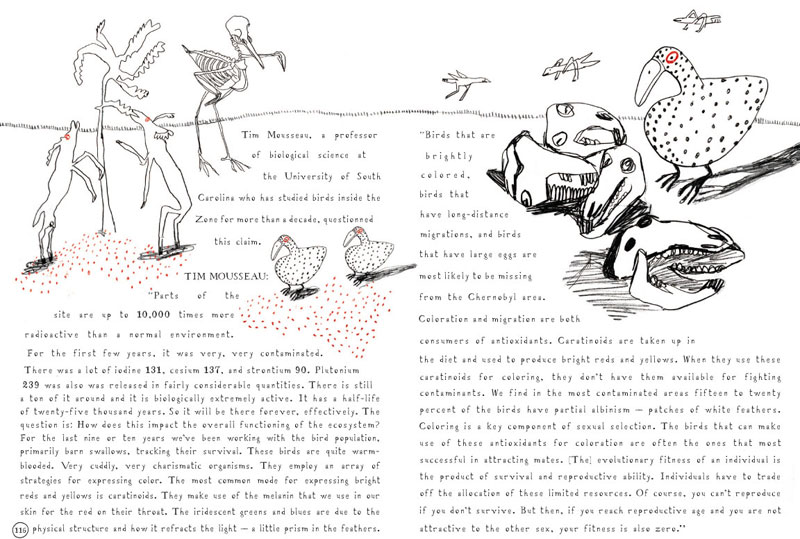

RADIOACTIVE

RADIOACTIVE

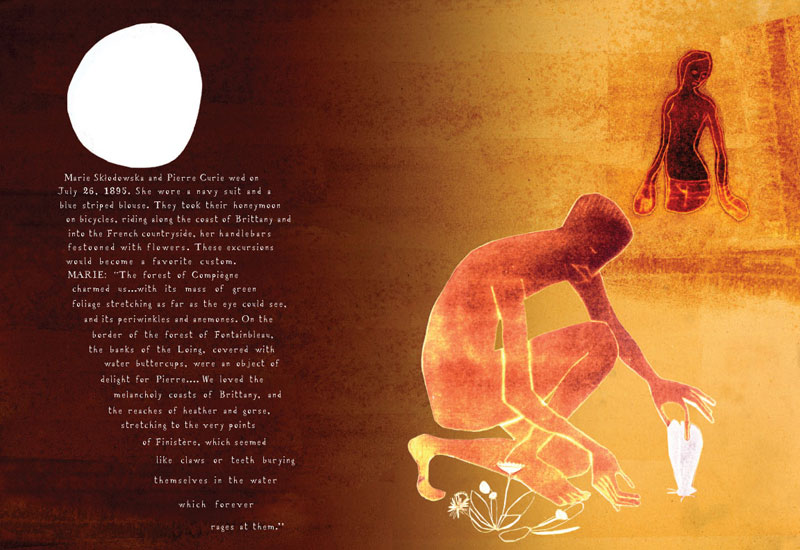

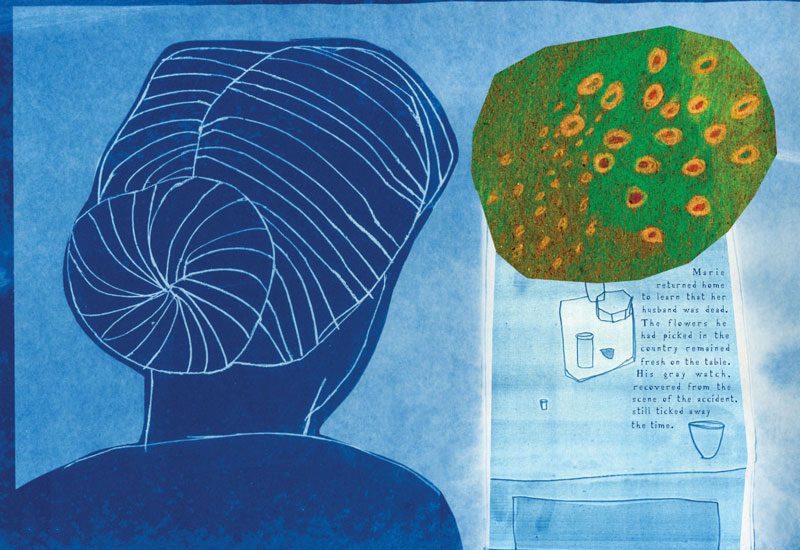

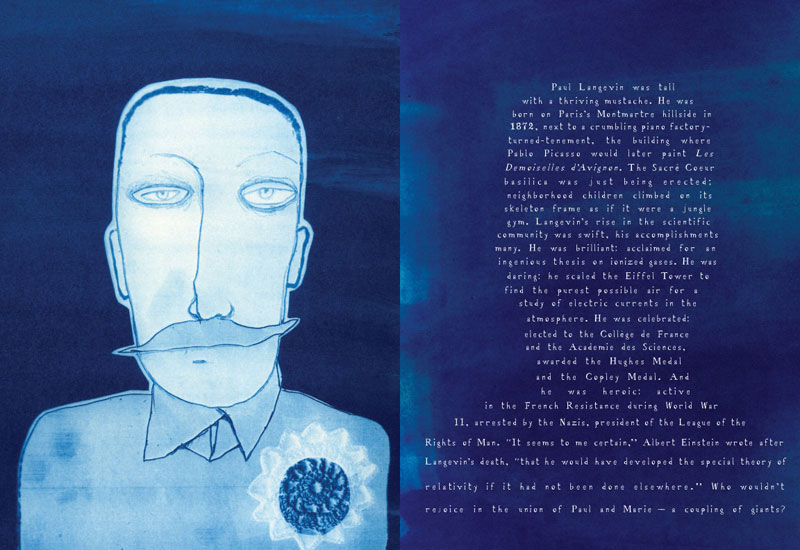

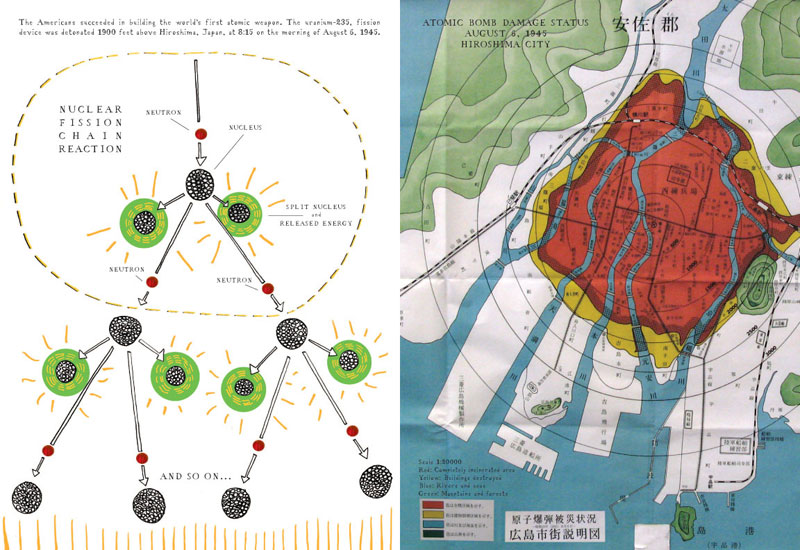

In Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie: A Tale of Love and Fallout, artist Lauren Redniss tells the story of Marie Curie

— one of the most extraordinary figures in the history of science, a

pioneer in researching radioactivity, a field the very name for which

she coined, and not only the first woman to win a Nobel Prize but also

the first person to win two Nobel Prizes, and in two different sciences —

through the two invisible but immensely powerful forces that guided her

life: radioactivity and love. Granted, the book was also atop my

omnibus of the year’s best art and design books

— but that’s because it’s truly extraordinary — a remarkable feat of

thoughtful design and creative vision. To honor Curie’s spirit and

legacy, Redniss rendered her poetic artwork in cyanotype, an

early-20th-century image printing process critical to the discovery of

both X-rays and radioactivity itself — a cameraless photographic

technique in which paper is coated with light-sensitive chemicals. Once

exposed to the sun’s UV rays, this chemically-treated paper turns a deep

shade of blue. The text in the book is a unique typeface Redniss

designed using the title pages of 18th- and 19th-century manuscripts

from the New York Public Library archive. She named it Eusapia LR, for

the croquet-playing, sexually ravenous Italian Spiritualist medium whose

séances the Curies used to attend. The book’s cover is printed in

glow-in-the-dark ink.

In Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie: A Tale of Love and Fallout, artist Lauren Redniss tells the story of Marie Curie

— one of the most extraordinary figures in the history of science, a

pioneer in researching radioactivity, a field the very name for which

she coined, and not only the first woman to win a Nobel Prize but also

the first person to win two Nobel Prizes, and in two different sciences —

through the two invisible but immensely powerful forces that guided her

life: radioactivity and love. Granted, the book was also atop my

omnibus of the year’s best art and design books

— but that’s because it’s truly extraordinary — a remarkable feat of

thoughtful design and creative vision. To honor Curie’s spirit and

legacy, Redniss rendered her poetic artwork in cyanotype, an

early-20th-century image printing process critical to the discovery of

both X-rays and radioactivity itself — a cameraless photographic

technique in which paper is coated with light-sensitive chemicals. Once

exposed to the sun’s UV rays, this chemically-treated paper turns a deep

shade of blue. The text in the book is a unique typeface Redniss

designed using the title pages of 18th- and 19th-century manuscripts

from the New York Public Library archive. She named it Eusapia LR, for

the croquet-playing, sexually ravenous Italian Spiritualist medium whose

séances the Curies used to attend. The book’s cover is printed in

glow-in-the-dark ink.

Redniss tells a turbulent story — a passionate romance with Pierre

Curie (honeymoon on bicycles!), the epic discovery of radium and

polonium, Pierre’s sudden death in a freak accident in 1906, Marie’s

affair with physicist Paul Langevin, her coveted second Noble Prize —

under which lie poignant reflections on the implications of Curie’s work

more than a century later as we face ethically polarized issues like

nuclear energy, radiation therapy in medicine, nuclear weapons and more.

Full review, with more images and Redniss’s TEDxEast talk, here.

THE PHYSICS BOOK

THE PHYSICS BOOK

Einstein famously noted that the most incomprehensible thing about the world is that it’s comprehensible. In The Physics Book: From the Big Bang to Quantum Resurrection, 250 Milestones in the History of Physics, acclaimed science author Clifford Pickover

offers a sweeping, lavishly illustrated chronology of comprehension by

way of physics, from the Big Bang (13.7 billion BC) to Quantum

Resurrection (> 100 trillion), through such watershed moments as

Newton’s formulation of the laws of motion and gravity (1687), the

invention of fiber optics (1841), Einstein’s general theory of

relativity (1915), the first speculation about parallel universes

(1956), the discovery of buckyballs (1985), Stephen Hawking’s Star Trek cameo (1993), and the building of the Large Hadron Collider (2009).

Einstein famously noted that the most incomprehensible thing about the world is that it’s comprehensible. In The Physics Book: From the Big Bang to Quantum Resurrection, 250 Milestones in the History of Physics, acclaimed science author Clifford Pickover

offers a sweeping, lavishly illustrated chronology of comprehension by

way of physics, from the Big Bang (13.7 billion BC) to Quantum

Resurrection (> 100 trillion), through such watershed moments as

Newton’s formulation of the laws of motion and gravity (1687), the

invention of fiber optics (1841), Einstein’s general theory of

relativity (1915), the first speculation about parallel universes

(1956), the discovery of buckyballs (1985), Stephen Hawking’s Star Trek cameo (1993), and the building of the Large Hadron Collider (2009).

The book, which could well be the best thing since Bill Bryson’s short illustrated history of nearly everything, begins with a beautiful quote about the poetry of science and curiosity:

As the island of knowledge grows, the surface that makes contact with mystery expands. When major theories are overturned, what we thought was certain knowledge gives way, and knowledge touches upon mystery differently. This newly uncovered mystery may be humbling and unsettling, but it is the cost of truth. Creative scientists, philosophers, and poets thrive at this shoreline.” ~ W. Mark Richardson, ‘A Skeptic’s Sense of Wonder,’ Science

Pickover takes a wide-angle view of what physics actually is,

encompassing everything from relativity to quantum mechanics to dark

matter and beyond, in a spirit that honors the American Physical

Society’s founding mission statement of 1899, which holds physics as

“the most basic and fundamental science.” As much as it is about the

great ideas of physics, the book is also about the great minds behind

them, including Brain Pickings darlings Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, Richard Feynman, Stephen Hawking, and Erwin Schrödinger.

From the magnetic monopole to quasicrystals to dark matter, The Physics Book is an invaluable treasure trove of curated knowledge in an age when, as Andrew Zolli put it at the opening of PopTech

2011, “the scale of our knowledge is expanding faster than most of our

ability to comprehend.” For once, it’s rather nice to make some of

humanity’s greatest intellectual achievements feel contained and

digestible.

Originally reviewed, with plenty more images, last month.

I HAVE LANDED

I HAVE LANDED

For 27 years, iconic evolutionary biologist and science historian Stephen Jay Gould contributed illuminating and absorbing essays on everything from Aristotle to zoology for the magazine Natural History,

many collected in a series of anthologies, offering some of the most

articulate science writing of our time and influencing public opinion on

science in magnitude few other writers have achieved. This year marked

the bittersweet reprint of I Have Landed: The End of a Beginning in Natural History

— the tenth and final of these fantastic anthologies, featuring 31 of

Gould’s essays and commemorating the centennial of his family’s arrival

at Ellis Island. (The title comes from his grandfather’s diary entry on

that day.) It was originally published in 2002, mere weeks after Gould

passed away from cancer.

For 27 years, iconic evolutionary biologist and science historian Stephen Jay Gould contributed illuminating and absorbing essays on everything from Aristotle to zoology for the magazine Natural History,

many collected in a series of anthologies, offering some of the most

articulate science writing of our time and influencing public opinion on

science in magnitude few other writers have achieved. This year marked

the bittersweet reprint of I Have Landed: The End of a Beginning in Natural History

— the tenth and final of these fantastic anthologies, featuring 31 of

Gould’s essays and commemorating the centennial of his family’s arrival

at Ellis Island. (The title comes from his grandfather’s diary entry on

that day.) It was originally published in 2002, mere weeks after Gould

passed away from cancer.

From a fascinating essay on Vladimir Nabokov’s lepidoptery

poetically titled “No Science Without Fancy, No Art Without Facts” to a

meditation on Freud’s evolutionary fantasy to a poignant scientific

reflection on 9/11, the essays blend a head-spinning spectrum of serious

scientific inquiry with the storytelling of fine fiction.

In fact, a big part of what makes Gould’s thinking so compelling and

his writing so alluring is the eloquence with which he blends popular

interest with deep scientific insight. (The very notion of a scientific

essay faces a great deal of resistance among many scientists, who find

the essay format to be inappropriate for science.) Of the balance, Gould

writes:

I have come to believe, as the primary definition of these ‘popular’ essays, that the conceptual depth of technical and general writing should not differ, lest we disrespect the interest and intelligence of millions of potential readers who lack advanced technical training in science, but who remain just as fascinated as any professional, as just as well aware of the importance of science to our human and earthly existence.”

Gould closes his final essay for Natural History with this moving tribute to his grandfather, all the more profound in light of the author’s own passing shortly thereafter:

Dear Papa Joe, I have been faithful to your dream of persistence and attentive to a hope that the increments of each worthy generation may buttress the continuity of evolution. You could write those wondrous words right at the beginning of your journey, amidst all the joy and terror of inception. I dared not repeat them until I could fulfill my own childhood dream — something that once seemed so mysteriously beyond any hope of realization to an insecure little boy in a garden apartment in Queens — to

become a scientist and to make, by my own effort, even the tiniest addition to human knowledge of evolution and the history of life. But now, with my 300, so fortuitously coincident with the world’s new 1,000 and your own 100, perhaps I have finally won the right to restate your noble words and to tell you that their inspiration still lights my journey: I have landed. But I also can’t help wondering what comes next!”

Originally featured in October.

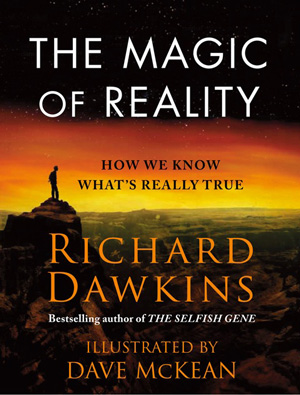

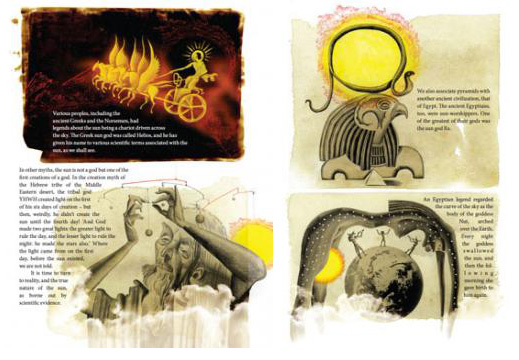

THE MAGIC OF REALITY

THE MAGIC OF REALITY

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins — who in 1976 famously coined the term “meme” in his seminal, must-read book The Selfish Gene — is nowadays best-known as the world’s most celebrated atheist. This year, Dawkins released his first sort-of-children’s book, The Magic of Reality: How We Know What’s Really True, also among the year’s best children’s books

— a scientific primer for the world, its magic, and its origin, an

antidote to the creationism mythology teaching young readers how to

replace myth with science, and a fine addition to our favorite soft-of-children’s nonfiction.

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins — who in 1976 famously coined the term “meme” in his seminal, must-read book The Selfish Gene — is nowadays best-known as the world’s most celebrated atheist. This year, Dawkins released his first sort-of-children’s book, The Magic of Reality: How We Know What’s Really True, also among the year’s best children’s books

— a scientific primer for the world, its magic, and its origin, an

antidote to the creationism mythology teaching young readers how to

replace myth with science, and a fine addition to our favorite soft-of-children’s nonfiction.

With beautiful illustrations by graphic artist Dave McKean,

Dawkins’ volume is as accessible as it is illuminating, covering a

remarkable spectrum of subjects and natural phenomena — from who the

very first person was to how earthquakes work to what dark matter is —

in a way that infuses reality with the kind of fascination and whimsy

we’re used to finding in myth and folklore. Each chapter begins with a

famous myth from one of the world’s religions or folklore traditions,

which Dawkins proceeds to myth-bust by examining the actual scientific

processes and phenomena that these stories try to explain.

Here’s an introduction from Dawkins himself:

BBC has a great short segment, in which Dawkins explores the

relationship between comfort and truth, and explains why evolution is

the most magical, spellbinding story of all, more poetic than any fable

or fairy tale:

When you think about it, here we are, we started off on this planet — this fragment of dust spinning around the sun — and in 4 billion years we gradually changed form bacteria into us. That is a spellbinding story.” ~ Richard Dawkins

The book comes with a companion immersive iPad app.

In an age when we’re still struggling to convince the powers that be of the value of public science and some public schools still perpetuate the mythology of creationism, Dawkins delivers a sober yet wildly absorbing and magical dose of reality in The Magic of Reality — one that brings to mind Jonah Lehrer’s reformulation of the famous Picasso quote: “Every child is a natural scientist. The problem is how to remain a scientist once we grow up.”

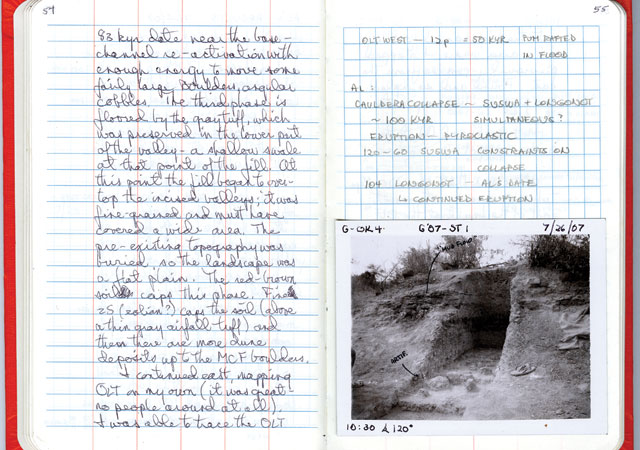

FIELD NOTES

FIELD NOTES

Field Notes on Science and Nature, one of five fascinating peeks inside the notebooks of great creators,

offers an unprecedented look at the inner workings of scientific

inquiry and observation. It’s as much a scientific travelogue as it is a

celebration of traditional methodologies for making sense of our

natural environment, its beautiful reproductions of original journal

pages taking us from Baja, California, with eminent ornithologist Kenn

Kaufman to the Serengeti with renowned mammalogist George Schaller.

Field Notes on Science and Nature, one of five fascinating peeks inside the notebooks of great creators,

offers an unprecedented look at the inner workings of scientific

inquiry and observation. It’s as much a scientific travelogue as it is a

celebration of traditional methodologies for making sense of our

natural environment, its beautiful reproductions of original journal

pages taking us from Baja, California, with eminent ornithologist Kenn

Kaufman to the Serengeti with renowned mammalogist George Schaller.

Michael Canfield, who edited the book and is himself a biologist at

Harvard, invites us to “peer over the shoulders of outstanding field

scientists and naturalists” through their brilliant annotations and

illustrations.

Image courtesy of the American Philosophical Society

Anna K. Behrensmeyer, Paleontologist, in the essay 'Linking Researchers Across Generations'

Roger Kitching, Ecologist, in 'A Reflection of the Truth'

The twelve essays in Field Notes

were written by professional naturalists from such diverse disciplines

as anthropology, botany, ecology, entomology, and paleontology, and

their enthusiasm and experience are contagious. For the amateur

naturalists among us, the compilation also contains essays on

“Note-Taking for Pencilophobes” and basic instructions on color theory

and sketching.

Jenny Keller, in the essay 'Why Sketch?'

E.O. Wilson articulates the book’s voyeuristic magic in its introduction:

If there is a heaven, and I am allowed entrance, I will ask for no more than an endless living world to walk through and explore. I will carry with me an inexhaustible supply of notebooks, from which I can send back reports to the more sedentary spirits (mostly molecular and cell biologists). Along the way I would expect to meet kindred spirits among whom would be the authors of the essays in this book.”

Kirstin Butler’s original review here.

FEYNMAN

FEYNMAN

Legendary iconoclastic physicist Richard Feynman is a longtime favorite, his insights on beauty, honors, and curiosity pure gold. Feynman is a charming, affectionate, and inspiring graphic novel biography from librarian by day, comic nonfictionist by night Jim Ottoviani and illustrator Leland Myrick, and a fine addition to our 10 favorite masterpieces of graphic nonfiction.

Legendary iconoclastic physicist Richard Feynman is a longtime favorite, his insights on beauty, honors, and curiosity pure gold. Feynman is a charming, affectionate, and inspiring graphic novel biography from librarian by day, comic nonfictionist by night Jim Ottoviani and illustrator Leland Myrick, and a fine addition to our 10 favorite masterpieces of graphic nonfiction.

From Feynman’s childhood in Long Island to his work on the Manhattan

Project to the infamous Challenger disaster, by way of quantum

electrodynamics and bongo drums, the graphic narrative unfolds with

equal parts humor and respect as it tells the story of one of the

founding fathers of popular physics.

Colorful, vivid, and obsessive, the pages of Feynman

exude the famous personality of the man himself, full of immense

brilliance, genuine excitement for science, and a healthy dose of snark.

Originally featured, with more images, in October.

CULTURE

CULTURE

This year, Edge.org editor John Brockman

launched a new series of anthologies curating 15 years’ worth of the

most provocative thinking on major facets of science, culture, and

intellectual life. First came The Mind, followed by Culture: Leading Scientists Explore Societies, Art, Power, and Technology

— a treasure chest of insight true to the promise of its title,

featuring essays and interviews by and with (alas, all-male) icons such

as Brian Eno, George Dyson and Douglas Rushkoff, as well as Brain Pickings favorites like Denis Dutton, Stewart Brand, Clay Shirky and Dan Dennett.

From the origin and social purpose of art to how technology shapes

civilization to the Internet as a force of democracy and despotism, the

17 pieces exude the kind of intellectual inquiry and cultural curiosity

that give progress its wings.

This year, Edge.org editor John Brockman

launched a new series of anthologies curating 15 years’ worth of the

most provocative thinking on major facets of science, culture, and

intellectual life. First came The Mind, followed by Culture: Leading Scientists Explore Societies, Art, Power, and Technology

— a treasure chest of insight true to the promise of its title,

featuring essays and interviews by and with (alas, all-male) icons such

as Brian Eno, George Dyson and Douglas Rushkoff, as well as Brain Pickings favorites like Denis Dutton, Stewart Brand, Clay Shirky and Dan Dennett.

From the origin and social purpose of art to how technology shapes

civilization to the Internet as a force of democracy and despotism, the

17 pieces exude the kind of intellectual inquiry and cultural curiosity

that give progress its wings.

Here’s a modest sampling of the lavish cerebral feast you’ll find between the book’s covers.

In his 1997 meditation “A Big Theory of Culture”, music icon and deep-thinker Brian Eno explores what constitutes cultural value and how it comes about:

Nearly all of art history is about trying to identify the source of value in cultural objects. Color theories and dimension theories, golden means, all those sort of ideas, assume that some objects are intrinsically more beautify and meaningful than others. New cultural thinking isn’t like that. It says that we confer value on things. We create the value in things. It’s the act of conferring that makes things valuable. Now this is very important, because so many, in fact all fundamentalist ideas, rest on the assumption that some things have intrinsic value and resonance and meaning. All pragmatists work from another assumption: No, it’s us. It’s us who make those meanings.”

In “Art and Human Reality” (2009), the late and great Arts & Letters Daily editor Dennis Dutton made an early case for provocative Darwinian theory of beauty:

[It] is not some kind of ironclad doctrine that it is supposed to replace a heavy post-structuralism with something just as oppressive. What surprises me about the resistance to the application of Darwin to psychology is the vociferous way in which people want to dismiss it, not even to consider it.”

In “Social Networks Are Like the Eye” (2008), Harvard physician and sociologist Nicholas Christakis examines why networks form and how they operate:

The amazing thing about social networks, unlike other networks that are almost as interesting — networks of neurons or genes or stars or computers or all kinds of other things one can imagine — is that the nodes of a social network — the entities, the components — are themselves sentient, acting individuals who can respond to the network and actually form it themselves.”

In “Turing’s Cathedral” (2005), science historian George Dyson recalls his visit to the Google headquarters in the context of H. G. Wells’s 1938 prophecy:

I felt I was entering a 14th-century cathedral — not in the 14th century but in the 12th century, while it was being built […] The whole human memory can be, and probably in a short time will be, made accessible to every individual […] Wells foresaw not only the distributed intelligence of the World Wide Web, but the inevitability that this intelligence would coalesce, and that power, as well as knowledge, would fall under its domain.”

Thoughtfully curated to stimulate your keenest critical thinking — like, for instance, the juxtaposition of Jaron Lanier’s digital dystopianism and Clay Shirky’s optimistic retort — Culture expands both the scope of science and your comfort zone of intellectual inquiry.

THE MAN OF NUMBERS

THE MAN OF NUMBERS

Imagine

a day without numbers — how would you know when to wake up, how to call

your mother, how the stock market is doing, or even how old you are? We

live our lives by numbers. So fundamental are they to our understanding

of the world that we’ve grown to take them for granted. And yet it

wasn’t always so. Until the 13th century, even simple arithmetic was

accessible almost exclusively to European scholars. Merchants kept track

of quantifiables using Roman numerals, performing calculations either

by an elaborate yet widespread fingers procedure or with a clumsy

mechanical abacus. But in 1202, a young Italian man named Leonardo da Pisa — known today as Fibonacci — changed everything when he wrote Liber Abbaci, Latin for Book of Calculation, the first arithmetic textbook of the West.

Imagine

a day without numbers — how would you know when to wake up, how to call

your mother, how the stock market is doing, or even how old you are? We

live our lives by numbers. So fundamental are they to our understanding

of the world that we’ve grown to take them for granted. And yet it

wasn’t always so. Until the 13th century, even simple arithmetic was

accessible almost exclusively to European scholars. Merchants kept track

of quantifiables using Roman numerals, performing calculations either

by an elaborate yet widespread fingers procedure or with a clumsy

mechanical abacus. But in 1202, a young Italian man named Leonardo da Pisa — known today as Fibonacci — changed everything when he wrote Liber Abbaci, Latin for Book of Calculation, the first arithmetic textbook of the West.

Keith Devlin tells his incredible and important story in The Man of Numbers: Fibonacci’s Arithmetic Revolution,

tracing how Fibonacci revolutionized everything from education to

economics by making arithmetic available to the masses. If you think the

personal computing revolution of the 1980s was a milestone of our

civilization, consider the personal computation revolution. And yet, de

Pisa’s cultural contribution is hardly common knowledge.

The change in society brought about by the teaching of modern arithmetic was so pervasive and all-powerful that within a few generations people simply took it for granted. There was no longer any recognition of the magnitude of the revolution that took the subject from an obscure object of scholarly interest to an everyday mental tool. Compared with Copernicus’s conclusions about the position of Earth in the solar system and Galileo’s discovery of the pendulum as a basis for telling time, Leonardo’s showing people how to multiply 193 by 27 simply lacks drama.” ~ Keith Devlin

Image courtesy of The Library of Florence via NPR

Though “about” mathematics, Fibonacci’s story is really about a great number of remarkably timely topics: gamification for good (Liber abbaci brimmed with puzzles and riddles like the rabbit problem to alleviate the tedium of calculation and engage readers with learning); modern finance (Fibonacci was the first to develop an early form of present-value analysis, a method for calculating the time value of money perfected by iconic economist Irving Fisher in the 1930s); publishing entrepreneurship (the first edition of Liber Abbaci

was too dense for the average person to grasp, so da Pisa released —

bear in mind, before the invention of the printing press — a simplified

version accessible to the ordinary traders of Pisa, which allowed the

text to spread around the world); abstract symbolism

(because numbers, as objective as we’ve come to perceive them as, are

actually mere commonly agreed upon abstractions); and even remix culture (Liber Abbaci

was assumed to be the initial source for a great deal of arithmetic

bestsellers released after the invention of the printing press.)

Above all, however, Fibonacci’s feat was one of storytelling — much like TED,

he took existing ideas that were far above the average person’s

competence and grasp, and used his remarkable expository skills to make

them accessible and attractive to the common man, allowing these ideas

to spread far beyond the small and self-selected circles of the

scholarly elite.

Image courtesy of Siena Public Library via NPR

A book about Leonardo must focus on his great contribution and his intellectual legacy. Having recognized that numbers, and in particular powerful and efficient ways to compute with them, could change the world, he set about making that happen at a time when Europe was poised for major advances in science, technology, and commercial practice. Through Liber Abbaci he showed that an abstract symbolism and a collection of seemingly obscure procedures for manipulating those symbols had huge practical applications.” ~ Keith Devlin

For an added layer of fascinating, there’s also a complementary ebook titled Leonardo and Steve, drawing a curious parallel between Fibonacci and Steve Jobs.

Originally featured, with a Kindle preview, in July.

FUTURE SCIENCE

FUTURE SCIENCE

What consumes the best and brightest minds working in science today? That’s exactly what literary agent Max Brockman explores in Future Science: Essays from the Cutting Edge

— a fantastic anthology of short pieces by 19 first-rate researchers

spanning everything from astronomy to virology to computer science, and a

wealth in between. The provocative yet digestible essays are intended

for the curious layperson, which Brockman reminds us in the introduction

doesn’t come without risk: “If you’re an academic who writes about your

work for a general audience, you’re thought by some of your colleagues

to be wasting your time and perhaps endangering your academic career.

For younger scientists (i.e., those without tenure), this is almost

universally true.”

What consumes the best and brightest minds working in science today? That’s exactly what literary agent Max Brockman explores in Future Science: Essays from the Cutting Edge

— a fantastic anthology of short pieces by 19 first-rate researchers

spanning everything from astronomy to virology to computer science, and a

wealth in between. The provocative yet digestible essays are intended

for the curious layperson, which Brockman reminds us in the introduction

doesn’t come without risk: “If you’re an academic who writes about your

work for a general audience, you’re thought by some of your colleagues

to be wasting your time and perhaps endangering your academic career.

For younger scientists (i.e., those without tenure), this is almost

universally true.”

Given our optimism for the future and soft spot for intellectual anthologies, we’re certainly glad the contributors to Future Science

took the chance. The result is a fascinating tour of academy’s advanced

guard on, among other topics, why stress causes some people to crumble

even as it spurs others on, what sense computer science can make of

social media’s vast digital data, and how infinity has entered the realm

of testable science. The breadth of subjects and their authors’ ability

to make them accessible is thrilling — it’s like TED in book form.

Here’s just a small sampling from Future Science‘s contents:

For much of human history, we have been explorers of other continents — examiners of rocks and regions ripe for habitation, the culmination being the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration and the capstone being our flags and footprints on the surface of the Moon. But in the decades and centuries to come, exploration — both human and robotic — will increasingly focus on the ocean depths, of both our own ocean and the subsurface oceans believed to exist on at least five moons of the outer Solar System: Jupiter’s Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto and Saturn’s Titan and Enceladus. The total volume of liquid water on those worlds is estimated to be more than a hundred times the volume of liquid water on Earth.” ~ Kevin P. Hand, “On the Coming Age of Ocean Exploration”

If humans are to succeed as a species, our collective shame over destroying other life-forms should grow in proportion to our understanding of their various ecological roles. Maybe the same attention to one another that promoted our own evolutionary success will keep us from failing the other species in life’s fabric and, in the end, ourselves.” ~ Jennifer Jacquet, “Is Shame Necessary”

This afternoon I received in the post a slim FedEx envelope containing four small vials of DNA. The DNA had been synthesized according to my instructions in under three weeks, at a cost of 39 U.S. cents per base pair (the rungs adenine-thymine or guanine-cytosine in the DNA ladder). The 10 micrograms I ordered are dried, flaky, and barely visible to the naked eye, yet once I have restored them in water and made an RNA copy of this template, they will encode a virus I have designed.” ~ William McEwan, “Molecular Cut and Paste: The New Generation of Biological Tools”

As you might have guessed, Brockman is the son of John Brockman, who masterminded Culture above.

No comments:

Post a Comment